TRUTH & RECONCILIATION

How do we reclaim the millions who have been wounded by the countless episodes of man’s gross inhumanity to man? Often, these tragedies have been the result of institutional collaboration where the least and the lost among us were acted upon in a manner that created a disregard of, a demonization of, a marginalization of, a victimization of a sector of our communities whose very presence displays our collective shortcomings. Then there is also the damage to the soul of the perpetrators. These wounds destroy our present and our future by trapping many in the past with all of the memories of harm, destruction and damage from these horrific events.

Horrific events lead to horrific consequences. What could be a more horrific consequence than an event in which the institutions of our “civilization” create an environment where, as a society, we collectively abandon our pursuit of relationships that affirm and realize the equality, dignity, worth and potential of each individual? There have been repeated attempts to get us to abandon that course: Spain, Peru, Chile, Argentina, Ghana, Guatemala, East Timor have all experienced such events. The history of the United States is filled with such occurrences from the period of enslavement, the massacre of the indigenous population through the environmental racism of today where monumental instances of injustice threaten to undermine our higher calling as a society, affirming and realizing “the equality, dignity, worth and potential of each individual.”

Without healing, these horrific occurrences would continue to control and define the people who had experienced these breeches in our humanity and limit the potential of all involved. Healing must take place. Healing for the victims/survivors. Healing for the perpetrators. Healing for the community. Great thinkers, in facing this fact realized that something needed to be done to allow the light of healing to shine on these blights on our humanity.

In 1974 in Uganda, a process known as a truth commission was first utilized to effect healing in a victimized people. A truth commission is a process that seeks to “tell a version of history that includes the victims’ experiences and voices, recognizes their humanity and rights, and seeks to come to terms with abuse in all of its many dimensions. Truth commissions can help overcome false assumptions and myths about the past and identify policies and systematic practices at the heart of abuses.” These efforts can “help societies come to terms with how such a thing could happen and what must change in order to avoid similar abuses in the future.” Over 40 such efforts had been empanelled by 2005 with the South African Truth Commission being the most well known.

In the United States, the first such effort occurred in Greensboro, NC

On November 3, 1979 five people were murdered, ten people were wounded, four women and one man were widowed, and the community of Greensboro, North Carolina, was thrown into shock and confusion. Four television crews captured the killings on film. Nevertheless, the perpetrators, members of the American Nazi Party and the Ku Klux Klan, were twice acquitted of any wrongdoing, in state and federal courts. Eventually, several Klan members, Nazis and Greensboro police officers were found jointly liable for one of the deaths. The City of Greensboro paid a $351,000 settlement to survivors of the tragedy, but it never fully acknowledged nor apologized for its role. A full accounting of the relevant factors of this well-documented tragedy has not yet been entered into the public record and public consciousness.

The Greensboro Truth and Community Reconciliation Project sought to provide opportunities for the entire city to heal and to come to a clear understanding of the events of November 3, 1979 and their aftermath. The hope was to reach an understanding based on careful and honest reexamination of the roles of the various actors, groups, and institutions, as well as the role of the ordinary citizen. To this end, a commission composed of people with integrity and a variety of gifts, who were willing to commit themselves to seeking the truth amidst all the data and perspectives surrounding this complex situation, was be created.

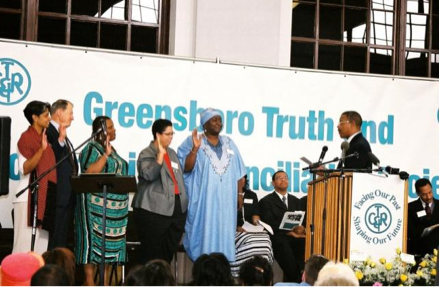

The Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission spent over 2 years in hearing a variety of testimony, reviewing documents, and hosting public forms across Greensboro. The result of their work was a well written 529 page report, that included 29 recommendations for the city of Greensboro. The Beloved Community Center and other organization see the recommendations as steps to positive change in relationships in Greensboro. The Final Report of the Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission can be found here: FINAL REPORT!

5TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE RELEASE OF THE TRUTH REPORT

THE GREENSBORO TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COLLECTION

Summary Information

Title: Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Collection

Date/Date Range: November 3, 1979 – May 25, 2008

Extent: 369 linear feet

Series number: A100

Repository: Bennett College Archives, Thomas F. Holgate Library, Bennett College for Woman, Greensboro, North Carolina

Collection Scope and Content Note: This collection contains documents concerning the fatal clash between members of the Communist Workers Party (CWP) and members of the Ku Klux Klan and the Nazi Party which occurred on November 3, 1979, as well as the subsequent investigation and findings of the Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission (GTRC). This collection includes correspondence, hearing transcripts, court documents, newspaper clippings, pamphlets, posters, audio/visual material and photographs, manuscripts, and other materials documenting these events.

Provenance: This collection is comprised of documents collected by the GTRC from several different sources. The material within these separate sources was organized, documented, and forwarded to Bennett College for Women at the completion of the work done by the GTRC. The original system of documentation of these separate sources was incorporated into the organizational structure of the final collection.

Abstract: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission was formed in response to an incident, which occurred on November 3, 1979, in Greensboro, North Carolina. On this date, there was a clash between the Communist Workers Party (CWP) and members of the Ku Klux Klan and the Nazi Party in the Morningside Homes community during a "Death to the Klan" demonstration. This event resulted in the deaths of César Cauce, Michael Ronald Nathan, M.D., William Sampson, Sandra Neely Smith (student and SGA president of Bennett College), and James Waller, M.D., and the wounding of demonstrators Paul Bermanzohn, Claire Butler, Tom Clark, Nelson Johnson, Rand Manzella, Don Pelles, Frankie Powell, Jim Wrenn; Klansman Harold Flowers; and news photographer David Dalton. There were subsequently two criminal trials and a civil trial which found the Greensboro Police Department (GPD), and members of the Nazi Party and Ku Klux Klan, jointly liable in the death of one activist. In an attempt to place this incident within a broader social context and to attempt restorative justice in this matter, the Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission (GTRC) was formed. Seven people, nominated by the community, formed an independent panel comprised of members of diverseracial, religious, and economic groups. The commissioners were sworn in on June 12, 2004, in Greensboro, North Carolina, as the nation’s first truth and reconciliation commission. The commission published the results of their careful compilation of facts and material in a report dated May 25, 2006. This final report recounts their findings, suggests institutional reforms, civil remedies, and strong civic engagement in the future to heal the "deep divides of distrust and skepticism in our community."